Claire Adam’s sophomore novel, Love Forms, is a tender and emotionally complex exploration of what it means to love, to lose, and to long for connection. Best known for her debut Golden Child, which won the Desmond Elliott Prize, Adam turns her attention from the external pressures of family honour and fate to the interior landscape of a woman grappling with the ghosts of her past. Set against the lush yet complicated backdrop of Trinidad, and sweeping through London, Venezuela, and Italy, Love Forms offers a moving meditation on the many ways love endures—even when tested by time, distance, and regret.

ALSO SEE: Book review: The Ex Effect by Jo Watson

Summary

At fifty-eight, Dawn Bishop is supposed to be entering a new phase of life. Divorced, with two adult sons and a quiet London flat to herself, she should feel a sense of peace. But instead, she is haunted. More than forty years ago, as a teenager in Trinidad, Dawn was sent away to Venezuela to give birth in secret and surrender her baby for adoption—a shameful solution orchestrated by her status-conscious parents to preserve the family’s reputation.

Now, decades later, with that child on her mind more than ever, Dawn sets out on a deeply personal journey to reconnect with her lost daughter. What follows is both a physical search across countries and a reckoning with her own identity, choices, and longing. Along the way, Love Forms examines the architecture of memory, the complexities of family, and the enduring nature of maternal love.

The review

A mother’s grief, softened by time but never silenced

Adam excels at capturing the quiet ache of a life shaped by what has been lost. Dawn’s longing for the daughter she never knew doesn’t erupt in melodrama—it simmers, influencing every part of her life. Her relationships with her sons, Finlay and Oscar, are loving but shaded by unresolved grief. Her former marriage, her career decisions, even her sense of self, all circle back to that defining moment at sixteen.

The portrayal of this grief—long, low, and lived—is one of the book’s great strengths. Readers won’t find tear-jerking scenes of reunion here, but rather an honest, contemplative portrait of what it means to live with absence.

A vivid sense of place

Adam’s descriptions of Trinidad are rich with colour and contradiction. The 1980s oil boom forms a shimmering backdrop to Dawn’s early years, with its promise of upward mobility and social standing. The Bishop family runs a successful fruit juice business, and with that success comes pressure to protect appearances at all costs. In contrast, her later journey through Venezuela, with her brother Warren by her side, is infused with a sense of danger, memory, and emotional weight.

These settings are not just decorative—they’re integral to the novel’s emotional landscape. Trinidad’s warmth, Venezuela’s disquiet, and London’s grey solitude all mirror different stages of Dawn’s emotional state.

Family dynamics and unspoken rules

The Bishop family isn’t cruel—but they are complicit. The social norms that dictated Dawn’s teenage exile were common, and Adam captures this with quiet devastation. There is no cartoon villain here, just a network of respectability politics and whispered expectations. Dawn’s brother Warren, hardened by time and loss, emerges as one of the novel’s most sympathetic characters, a man who navigates grief in his own guarded way, but ultimately supports Dawn’s journey with quiet loyalty.

These familial relationships, both supportive and strained, are rendered with nuance. Readers familiar with Caribbean cultures will recognise the subtle codes of honour and shame, while those less familiar will still appreciate the delicate way Adam lays these dynamics bare.

A story told in fragments—memory as architecture

Adam structures the novel with a fluidity that mirrors memory itself. Dawn’s reflections unfold gradually, drifting between past and present in a way that feels organic and authentic. There’s no info-dump here—just a slow, steady revelation of character through recollection.

This technique occasionally results in a lack of narrative momentum, particularly in the middle section of the novel, where Dawn’s day-to-day life in London feels a bit too subdued. But once she begins actively retracing her steps and reconnecting with people and places from her past, the story regains its emotional urgency.

The emotional cost of reunion

Unlike many novels about adoption or lost children, Love Forms doesn’t build toward a tidy resolution. The focus remains firmly on Dawn, her emotional evolution, her self-forgiveness, and her decision to confront rather than bury her past.

Her interactions with Monica Sartori, a possible DNA match in Italy, are poignant and real. Adam doesn’t lean on tropes or melodrama; she understands that reconnection—if it even happens—is fraught, tentative, and deeply personal. The story respects this emotional complexity and doesn’t try to resolve it too neatly.

Final thoughts

Love Forms is not a fast-paced or plot-heavy novel—it’s a quiet, introspective work that rewards patience and empathy. Claire Adam proves herself once again as a writer of great emotional intelligence, capable of giving voice to characters whose pain is often too quiet to name.

While the novel occasionally stumbles in pacing and could benefit from tighter structural focus, its strengths far outweigh its flaws. Dawn Bishop’s story lingers long after the final page—not because of dramatic twists or cinematic payoffs, but because it feels so intimately real.

This is a book for readers who appreciate layered character studies, Caribbean settings, and meditations on motherhood, migration, and memory. In Love Forms, Adam shows us how love, like identity, can take many shapes, often formed in the spaces left behind.

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

A slow burn, but a deeply rewarding one.

(* I received an advanced copy from Jonathan Ball Publishers).

ALSO SEE:

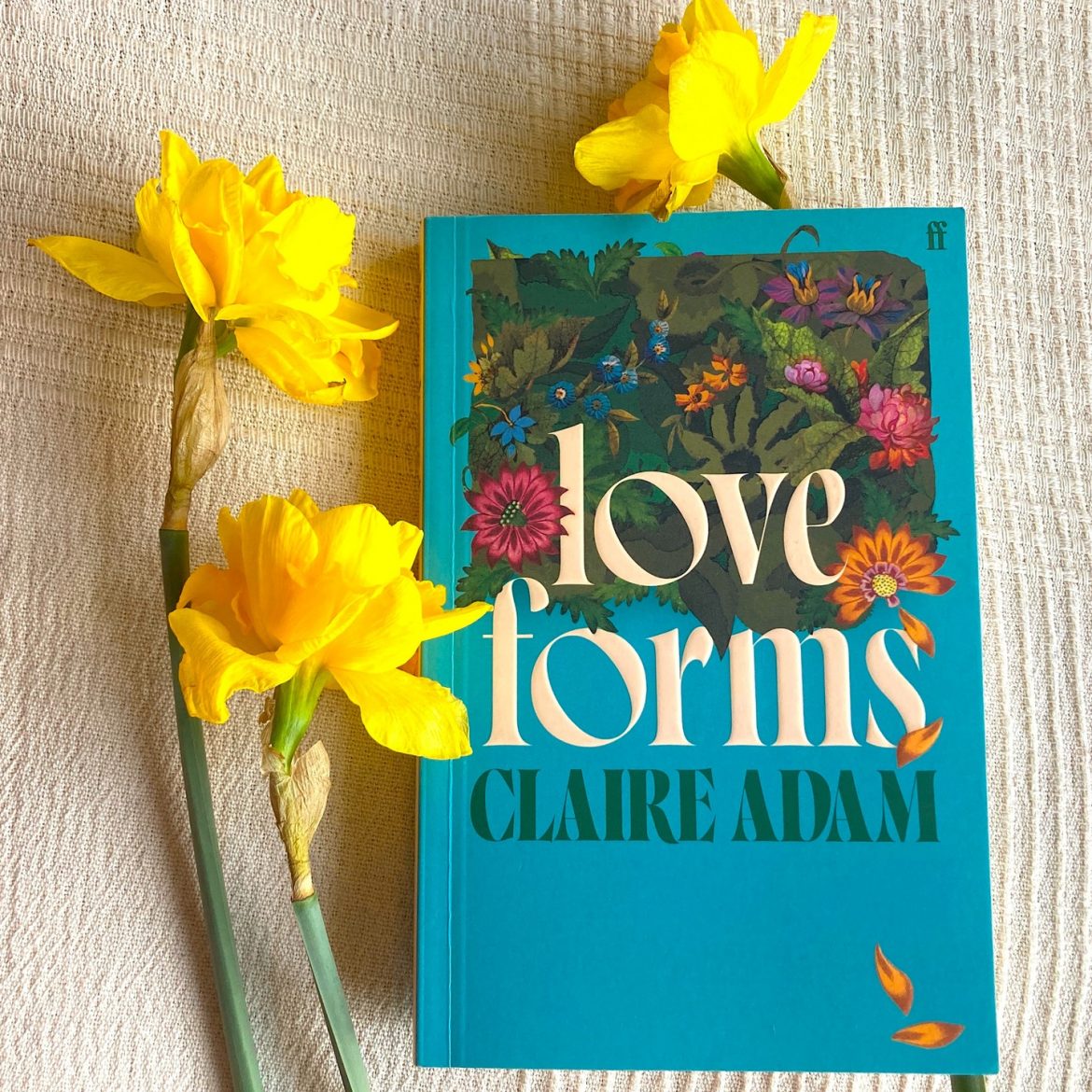

Featured Image: Instagram | claireadamwriter